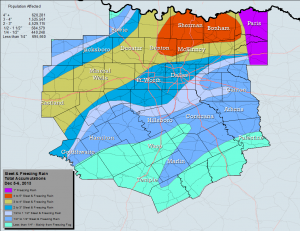

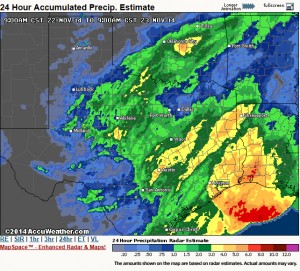

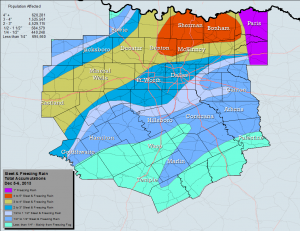

A major winter storm gripped most of North and Central Texas from December 5th through the 10th, 2013, severely impacting travel and power throughout the region. Freezing rain, sleet, and a little snow began falling during the afternoon of the 5th, and persisted through the morning hours of the 6th. As dawn broke on December 6th, a thick layer of ice encased much of North and Central Texas. Just about everyone north of a Goldthwaite to Hillsboro to Palestine line had ice on the ground at this point, including the entire DFW Metroplex. Sleet and ice measured as deep as 5″ in some areas, particularly in a swath extending from Denton, through Sherman, to Bonham.

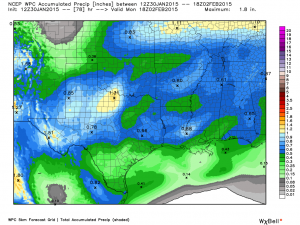

Ice accretion amounts across DFW from the “Cobblestone” ice storm that hit the area exactly one year ago. Map courtesy of the National Weather Service Office in Fort Worth, Texas.

As challenging as these fresh accumulations were for residents and travelers, the prolonged cold would make things worse. Temperatures dropped below freezing late in the day on the 5th, and would remain in the ice box for most of the next 5 days. The recurring combination of tire compaction, melting/re-freezing, and sand treatment would transform the initial frozen precipitation into rock hard formations, which would eventually be referred to as “cobblestone ice”. Most area streets and highways in the Metroplex and points north were subjected to these challenging conditions, forcing residents to remain at home for several days. Further south, conditions were a bit better, though ice did linger on bridges, overpasses, and elevated surfaces. Hundreds of cars and trucks were stranded for long periods on many of the main highways, particularly Interstate 35 from Fort Worth to the Oklahoma border, and Interstate 20 from Fort Worth going west.

While travel disruption was a major impact from this winter storm, power and property were others. Thousands of tree branches and power lines were downed by the weight of ice, particularly from Fort Worth, north and east to Paris. At the peak of the storm, 275,000 customers were without power in the North Texas region. Ice-laden tree branches crashed into vehicles, homes and other structures, sending thousands of residents scrambling for their insurance adjusters. Early estimates from the Insurance Council of Texas topped $30 million in residential insured losses. This figure did not include damage to vehicles or roads. Many roads and bridges were directly damaged from the ice – or from attempts to remove the ice using plows and graders. The clean-up from this event took weeks and even a few months in some places.

Most schools, especially in the hardest hit areas, were closed for several days, and thousands of businesses were forced to close for at least a day or two. Airlines at DFW Airport and Dallas Love Field cancelled hundreds of flights, and thousands of flyers were sheltered at both airports during the storm. Seven fatalities occurred during this event; 4 in vehicles, 2 from exposure, and 1 from a fall on the ice. Hundreds of injuries were also reported due to falls on the ice.

A Little More About Cobblestone Ice. Why Did It Form?

One of the most memorable aspects of this particular storm was the introduction of “cobblestone ice” into the common vocabulary of North Texans. So why did it form, and why did it get so bad?

First off, it goes without saying that there was an abundance of precipitation with this event. Many areas received over an inch of liquid, including DFW Airport, where 1.25” of liquid was observed. North and east of the Metroplex, totals were even higher. This translated into multiple inches of snow, sleet and/or freezing rain which existed in layers of varying depth. As traffic and marginal air and ground temperatures began to work on this frozen mess, some of it melted partially and morphed into slush during the daytime hours. Once nighttime fell, however, most of it would refreeze and harden. Despite the best efforts of local and state road crews, this cycle of compaction, melting, refreezing and hardening repeated itself in some areas over a period of up to 4 days.

In some spots, particularly on bridges and overpasses, larger chunks of ice were broken out of the icepack by plows and traffic. These chunks would mix in with the slush during the daytime, forming a soupy gray mess. At night, the entire concoction would refreeze, producing large molded bumps that were essentially glued to the very top of the roadways (or bridge decks). It was these hard, rock-like formations that represented the essence of the cobblestone ice experience for North Texas drivers.

Once frozen in place, this unique ice proved quite difficult to remove. Depths ranged from ½” to 4”, depending on where traffic caused peaks and valleys in the slush before it froze into cobblestone form.

While not a frequent occurrence, winter precipitation is no stranger to North and Central Texas. Fortunately, the cobblestone ice phenomenon is quite unusual. In addition to the magnitude of ice, it was the sustained period of cold temperatures following the event – interspersed with episodes of melting – that promoted the rough driving conditions. The only sure way to prevent this from happening in the future will be to remove most of the sleet and snow from the roadways before it gets a chance to melt and refreeze. Unfortunately, it may be difficult for local and state public works and transportation departments to achieve this lofty goal, given the thousands of miles of roadways under their jurisdictions. Having said this, local cities and counties, the State of Texas, and the National Weather Service in Dallas/Fort Worth did learn a great deal from the December 6th, 2013 storm – and these lessons will surely benefit all of North and Central Texas during future events.